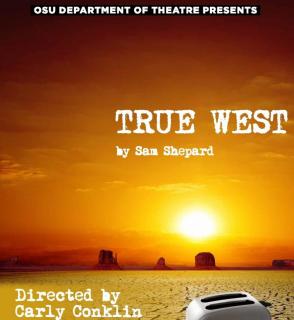

Review: TRUE WEST at OSU Department Of Theatre

In the director's note to the production of True West currently running at the OSU Department of Theatre in Stillwater, Carly Conklin quotes playwright Sam Shepard's reflection on his own script: "I wanted to write a play about double nature, one that wouldn't be symbolic or metaphorical or any of that stuff. I just wanted to give a taste of what it feels like to be two-sided." Shepard's insistence on a lack of symbolism and metaphor seems almost tongue in cheek - it is, of course, impossible to create a play in which characters embody the abstract concept of duality without toying with symbolism and metaphor. The crux of the play is this ever-present tension between a superficial realism and a self-referential indulgence of abstract ideas. In OSU's production, young actors present a formidable interpretation of the nuanced characters in this American masterwork.

In the director's note to the production of True West currently running at the OSU Department of Theatre in Stillwater, Carly Conklin quotes playwright Sam Shepard's reflection on his own script: "I wanted to write a play about double nature, one that wouldn't be symbolic or metaphorical or any of that stuff. I just wanted to give a taste of what it feels like to be two-sided." Shepard's insistence on a lack of symbolism and metaphor seems almost tongue in cheek - it is, of course, impossible to create a play in which characters embody the abstract concept of duality without toying with symbolism and metaphor. The crux of the play is this ever-present tension between a superficial realism and a self-referential indulgence of abstract ideas. In OSU's production, young actors present a formidable interpretation of the nuanced characters in this American masterwork.

True West tells the story of two brothers whose initially opposing and intermittently intersecting behaviors, ambitions, and anxieties are revealed while house-sitting in Southern California. The house belongs to their mother, who is vacationing in Alaska, and although she is absent until the final moments of the play, the artifacts of her carefully cultivated suburban life provide a perfect canvas for the brothers to gradually paint over. Indeed, the atmosphere on stage at the Jerry Davis Studio Theatre was brilliantly constructed by scenic designer Eric Barker and hauntingly lit by Denis Hutchinson. The steady destruction of the house and the beautifully eerie lighting shifts were central to maintaining the play's sense of disorientation and distorted identity.

When the play begins, Austin, played with sensitivity and hilarious unpredictability by Evan Houck, is house-sitting for their mother and attempting to work on his screenplay. Meanwhile, Lee, played by the captivating and fiery Devin Hite, drinks can after can of PBR and heckles him mercilessly. Austin is Ivy League educated, reserved, and dressed to match (by costume designer Renee Garcia): he presents like a caricature of a slightly shy and awkward member of the upper middle class. In contrast, Lee's speech is gruff, his shirt is stained, and he hobbles across the small space with a gargantuan presence. It is unclear if his gait is crippled by injury, alcohol, or affectation, but it doesn't matter. The brothers appear, of course, to be total opposites.

And yet, over the course of the play, their roles shift, sparked by the introduction of a third player: a film producer who is interested in Austin's work. This Hollywood titan is played by an appropriately sleazy and oblivious Tyrin Baldtrip, and ultimately Lee turns the tables on his brother: he seduces the producer into picking up his own movie idea instead, which is a classic Western flick hearkening back to the golden days of cinema. This triggers Austin's descent into outrage, drunkenness, and a night-long spree of toaster theft around the neighborhood. During this time, Austin begins an alcohol-fueled and contentious collaboration with his brother on the new movie script. At the end of the play, Mom finally comes home. Actress Mira Owens depicted her as completely shocked and incompetent to respond to her son's violently escalating shenanigans. After her departure, we're left only with a disturbing tableau, putting a distinctively dark seal on the preceding events.

The brothers' discussions about Lee's script are the best part of the play because they capture the simultaneous humor and tragedy inherent in attempting to create any kind of coherent narrative about heroism or right living. Much of the brothers' conversation is simply funny, or tense, or outright absurd: it's not all symbolism and metaphor. And yet ultimately, the discussion of the cowboys and their inexplicable triumphs and adventures belies the brothers' anxieties about who they are and the relationships they have with one another. When Lee describes the two cowboys in his film, he says, "Each one separately thinks that he's the only one that's afraid. [...] And the one who's chasin' doesn't know where the other one is taking him. And the one who's being chased doesn't know where he's going." Shepard is playing with metatheatricality here and it's endearingly self-deprecating: the Western film largely serves as a punchline to mock contrived plots and hackneyed storytelling conventions. And so its inclusion makes Austin and Lee all the more authentic because even as they echo various clichés, they disrupt them through self-reference.

Carly Conklin's direction and the performances from Houck and Hite struck this balance between maintaining a veneer of realism and allowing Shepard's more playful exploration of storytelling come to the foreground. True West is a play about things that change and those that cannot be changed, and any production must approach this delicately with an eye not just for character arcs but ebbs and flows of emotion. There was rarely an off moment when the two brothers were not hitting their stride and carrying us through their volatile emotional journey. Hite in particular approached the melodramatic moments with just enough explosive power without diminishing their credibility. Houck shone brightest in the second act when he was able to lean into the comedy and absurdity of his unraveling, and it was a joy to watch the two of them interact and bounce off of each other's energy.

True West surmounts the typical challenges of a college production, with the forgivable exception of failing to create entirely believable middle-aged/older characters. Overall, it's a striking rendition of a classic American play and an example of great college theatre. It would be utterly fascinating to see Houck and Hite test their theatrical dexterity by switching off in the leading roles, a gimmick used to great success with several Broadway productions of True West: and yet it is difficult to imagine rebalancing a production that is already so gracefully balanced.

Add Your Comment

Join Team BroadwayWorld

Are you an avid theatergoer? We're looking for people like you to share your thoughts and insights with our readers. Team BroadwayWorld members get access to shows to review, conduct interviews with artists, and the opportunity to meet and network with fellow theatre lovers and arts workers.

Interested? Learn more here.

Videos