Review: HAMILTON in Pittsburgh Is Everything You Hoped It Would Be

BUM. BA DA DA DUM. BUM. BUM. Wicky-woo.

Not since A Chorus Line has a musical's opening sting become this iconic (or iconic at all). The conventional wisdom that only one musical per decade can really matter in popular culture has not proven wrong; instead, Hamilton's success is at a level eclipsing RENT in the nineties or Wicked in the last decade. Those shows were popular musicals. Hamilton is a major cultural event, a milestone almost from the instant it premiered. I'm having trouble thinking back in time to find a musical as immediately significant in both the niche world of theatre, mainstream culture, and the critical world- sure, Jesus Christ Superstar was controversial and revolutionary, and Cabaret basically jump-started the punk and goth movement (look up the Bromley Contingent), but Hamilton feels different somehow. And four years into Hamiltonmania, not much has changed (success-wise and show-wise).

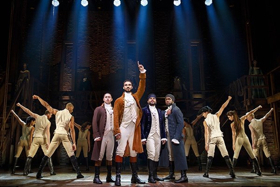

The story, told through the shifting perspective of a number of Revolutionary War and early American figures, asks the now-familiar (and oft-parodied) question of how a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence, impoverished, in squalor grew up to be a hero and a scholar. As the titular A. Ham, Austin Scott portrays the ten-dollar Founding father from adolescence to death, as the world and its perception of him both shift wildly.

Much has been written already about the ways replacement cast members for Hamilton have sometimes felt compelled to either follow faithfully in the footsteps of the idiosyncratic originals, or take alternate interpretations of the characters, and Austin Scott is a prime example. Alexander Hamilton, written for and originally played by the auteur Lin-Manuel Miranda himself, is typically played in one of two ways: either as an awkward, ambitious and oddly charming outsider (by Miranda), or as a suave, self-assured type (by everyone else who took on the role). Austin Scott definitely veers closer to the "sexy Hamilton" than "nerdy Hamilton" archetype, and though he doesn't rap with the same intense flow as Miranda, his singing outclasses the original easily, and he seems more at home in the role's acting requirements than Miranda. You can't fake charisma, and Miranda has that in spades, but it says something about the strengths of the role and of Scott's chops that he finds depths in the role that the iconic original could not.

Scott's counterpart, Josh Tower, has an equally demanding role. Aaron Burr carries a huge chunk of the show's musical demands, plus a number of rap passages which are made difficult by their relative verbal and rhythmic simplicity. Tower fits this role like a glove, and ironically his lyrical flow on the rap passages veers eerily close to Miranda's own higher-pitched, New York inflected rap style. Third in the triad of male leads who play only one role, Paul Oakley Stovall roots the show with a unique presence that differs notably from original Washington, Christopher Jackson. Visibly older-looking, with a large and solid physical presence, Stovall's George Washington feels less like a young idealist and more like the elder statesman of the group even in the character's younger days, and his deep voice recalls the tough-but-fair "chief" types played by Dennis Haysbert or Andre Braugher. This gruffness makes it especially cathartic when Washington first breaks into Washington's own prose in Act 2, and then finally belts out his biggest vocal passage near the end of "One Last Time."

Stephanie Umoh, late of Ragtime, is a thrilling Angelica, singing much in the standard style but spitting her furious rap in "Satisfied" with even more fire than the OBC. Hannah Cruz's Eliza is a warmer, more self-assured presence than Pippa Soo, but this stronger portrayal keeps Eliza from fading into the woodwork among the more flamboyant characters before "Burn" returns Hamilton's wife to active prominence in the storyline. (Also, in a show as aesthetically far-reaching in personal grooming as Hamilton, it's a close race, but Cruz definitely has the BEST DAMN HAIRCUT in the show.) As Peggy- I'm sorry, as "AND PEGGY"- Isa Briones is suitably snotty and sassy in her throwaway joke of a role, only to surprise later as the sultry, silky-voiced Maria Reynolds.

The supporting men get much of the best material, and Bryson Bruce is clearly reveling in his dual role as Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson. Bruce makes the roles, especially Jefferson, his own; lighter on his feet and a more natural dancer than Daveed Diggs, though without Diggs's deeply unusual vocal timbre, Bruce imbues his Jefferson with a manic sense of man-child physical comedy in the vein of Anthony Anderson. At times, Jefferson's compulsive dancing and grooving borders on minstrel show shucking and jiving, lending a dark irony to Jefferson's role as hypocritical slave owner/abuser. Chaunde Hall-Broomfield has a much less flashy role as sickly but level-headed hype man James Madison, but his blustering, roaring Hercules Mulligan in Act 1 more than makes up for it. Surprisingly, best in show goes to Jon Viktor Corpuz, in the usually thankless roles of John Laurens and Philip Hamilton. Between his pure, wide-ranging voice and his diminutive size, Corpuz is able to play a young revolutionary in the first act, and a preteen boy in the second act, with equal aplomb. Watching his bluster grow as Philip ages ten years in the second act was a highlight of the show. Last but not least, attention must be paid to Peter Matthew Smith, whose King George is rougher around the edges and madder than Groff's arch, preening original, lending the character a genuinely unpredictable feeling even though the role's blocking is still intentionally stagnant and minimal.

I like Hamilton a lot. It isn't my all-time favorite show, but it is one of the few shows I can watch or listen to in genuine awe at its construction and existence; Sweeney Todd is another on that very short list. Thomas Kail's physical production, aided by Andy Blankenbuehler's choreography, is already growing iconic, but it nonetheless feels almost... auxiliary? Superfluous might be a better word. Much like Jesus Christ Superstar, Hamilton lives and dies (and tells its story) based on the score and on the insane crossover hit cast recording, which made the jump from "sounding like a hit pop album" to "actually BEING a hit pop album in its own right." As such, actually seeing Hamilton live can sometimes feel less like seeing a hit musical and more like seeing a truly brilliant stage adaptation of a hit album that stood on its own two feet. This feeling of distance between the concept of Hamilton and the physical production of Hamilton is abetted by the Kail/Blankenbuehler staging, which fuses classic breakdancing, modern street and competition dance, and elements of avant-garde physical theatre. The stage images created in Hamilton are haunting, often minimalist tableaux, aided by the stage turntable in its most discussed role since it spun the barricade in Les Miserables. No one, listening to the album or making the inevitable film version, would picture a representation of the end of the Revolutionary War consisting of all the soldiers slowly raising their arms into T-pose, but in the moment it WORKS.

A fiinal word, lest I be accused of Hamilstanning: it might not be trendy or cutting-edge anymore to say "Hamilton is great, you should go see it," but the only reason people are sick of hearing that is because it's TRUE. We are still years out from the inevitable Hamilton backlash/reconsideration that every "defining musical of an era" gets. It's almost cliché these days to poke holes in RENT or Les Miserables or Wicked; we know the arguments against them by now and yet we know each show is more than the sum of its parts, and has remained a cultural mainstay for a reason. Hamilton is bigger than RENT, bigger than Les Miserables, maybe even bigger than The Phantom of the Opera. There is no precedent in modern memory for a show suddenly MATTERING so much almost from the moment it opened. So let's hold off on "what Hamilton does wrong and gets wrong" for another decade or so. This is not a moment, it's a movement. Let's let it move.

Videos