Review: THE ONE DAY OF THE YEAR at ARTS Theatre

By: Barry Lenny Aug. 19, 2018

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Saturday 18th August 2018.

Reviewed by Barry Lenny, Saturday 18th August 2018.

Are the lads no longer here,

I shall call - and you will waken

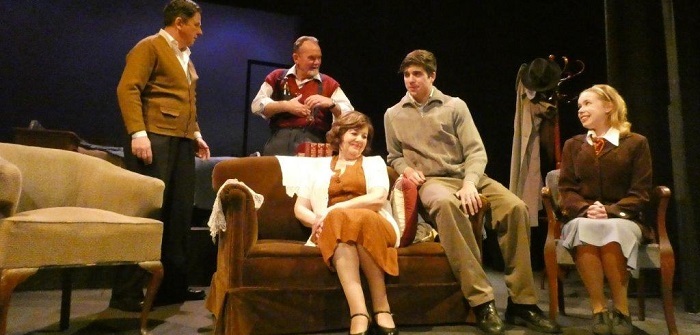

On this one day of the year. from: Landing in the Dawn, John Sandes, 1916. Initially, I found that the lines and moves were there, but the characters were often externalised, a little superficial. I was looking for more light and shade, and authentic emotions in the delivery of the dialogue. Lines often felt too hurried, skipping over the punctuation, sometimes lacking diction, and with raised voices passing for anger. It settled down after a while and, at times, genuine characters emerged. Alf Cook is an opinionated, ignorant, loudmouth, a xenophobe. He clings to his annual celebration, fondly remembering his time at war, as it is the only thing in his life of any importance to him. He is a lift operator, with dreams of moving up into an engineering position, refusing to accept that he has neither the qualifications nor experience and, of course, is too old for employers to take him on to learn on the job. Alf is played by John Rosen who gives us a character whom, for all of his bluster and belligerence, is a pathetic creature. Rosen's Alf leaves the audience hovering between laughing at this loser, angry at his outbursts, and even just a little sorry for him once in a while. Dot is aware of the divide growing between Alf and Hughie and spends much of her time mediating, and putting out the occasional spot fire, over copious amounts of tea, the great panacea, a cure for all ills. Dot and Alf have also grown apart and she now relates better to Wacka Dawson, a quieter, more thoughtful man, than to her husband. Julie Quick plays Dot in a warm portrayal of a wife and mother aware that her family is growing apart but trying to hold it together as long as possible. We can see the anguish in her performance and wonder what the future will bring. Wacka Dawson is a long-time friend of the family, once a friend of Alf's father before he was killed in WWI. Wacka fought in WWI and WWII, insisting that he lied about his age both times, being underage the first time and too old the second. He is, in fact, a true ANZAC, having been one of those on the beaches at Gallipoli. Alf is disappointed that Wacka, too, has decided not to march this year due to his leg injury, a war wound, making walking too difficult. Christopher Leech superbly underplays the role of Wacka, giving a subtle performance as the modest war hero, a quiet, gentle man. A highlight is when he and Quick sit together in the kitchen while the others are out, the two presenting fully realised characterisations, and engaging in a believable conversation. Jan Castle is from Sydney's upmarket North Shore, educated, wealthy, and well-spoken, and Alf immediately takes a dislike to her, telling Hughie that she is not 'their type'. Alf is still to recognise that, with his ongoing university education, Hughie is no longer 'their type', either, and moving farther away with every lecture or tutorial. Hughie is now caught between two worlds, no longer fitting in with his family due to his education, and not fitting into Jan's world because of his family background. It is ironical that Alf's insistence on Hughie getting ahead by going to university has resulted in driving them apart. Ashley Penny plays Jan, and Jai Pearce is Hughie, both of whom give rather mechanical performances that here and there hinted at characters starting to emerge. Hopefully, they will expand their performances as the season continues. The set has several levels, highest at the rear for Hughie's bedroom, slightly lower on the audience's left is the kitchen, and lower still to the right is the lounge. The kitchen, of course, is where much of the action takes place as that was the centre of the home, before electronic devices took over. Richard Parkhill's lighting helps to separate the locations. This is an important piece of Australian theatre so take the opportunity to see this play that caused such uproar when it first appeared.

Videos